Early vaccine for diphtheria developed in local laneway

By Mia Keskinen

Crestfallen Lane, located between Bathurst and Christie streets, north of Bloor, has a unique history, and its name pays homage to a horse, a doctor, and a vaccine. The lane name commemorates a mare named Crestfallen, a “miracle in a stable” purchased in 1913 by Dr. John G. Fitzgerald, who played a pivotal role in solving a public health crisis and developing vaccines.

More than 100 years ago, John Fitzgerald returned to Toronto after studying abroad and found the city amid a public health crisis: a diphtheria epidemic.

At the turn of the 20th century, diphtheria was considered the single greatest killer of children. Respiratory diphtheria is an upper respiratory tract illness which is sometimes deadly and causes serious health issues later in life.

The lower classes suffered the most; medicines imported from the United States were priced at extortionate costs, leaving many without means to fight the virus. “The city was rife with infectious diseases. Canadians forget how bad it was,” said Dr. FitzGerald’s grandson, James FitzGerald, in a Toronto Star article published in 2014.

COURTESY OF JAMES FITZGERALD

COURTESY OF JAMES FITZGERALD

Fitzgerald was determined to help the public in their time of need. He began by pitching his vision to the University of Toronto. He hoped to create a diphtheria antitoxin and distribute it freely to all Canadians as a public health service.

Given the University’s hesitance, the doctor took matters into his own hands.

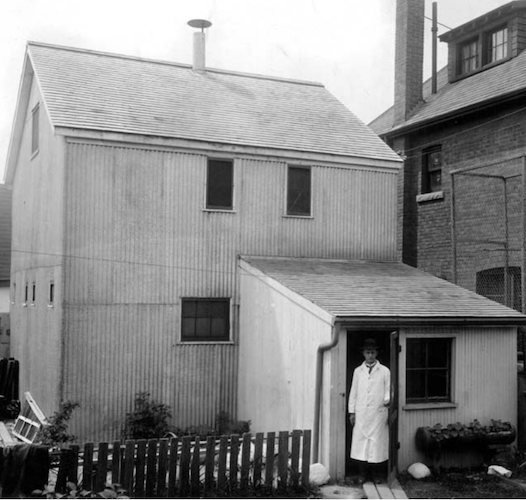

In 1913, Fitzgerald took $3000 from his wife’s dowry and built a horse stable with a lab for developing an antitoxin on 145 Barton Avenue. He then saved several elderly horses from a local glue factory. He named one of the horses Crestfallen because of her sad eyes.

On Dec. 11, 1913, Fitzgerald injected Crestfallen with a small dose of diphtheria. The horse built an immunity to diphtheria over four months due to gradual injections of diphtheria.

The blood was processed to create an antitoxin and tested on guinea pigs. After positive testing on humans, the vaccine was distributed to the lower classes as a public health service.

Fitzgerald single-handedly solved the diphtheria epidemic, and his work in the Canadian health-care industry helped to change the system.

James Fitzgerald said that “my grandfather’s inspired vision was transforming Canada’s public health system into a world leader.”

In 2014, the neighbourhood between Bathurst and Christie streets where the original lab was built, faced a public safety concern.

The houses within this neighborhood were built with little space separating each building, so homeowners accessed their properties through laneways behind their houses, each of which were unnamed.

When a house in the residential area caught fire, emergency crews struggled to find the location of the burning building, given the confusing labyrinth of unnamed laneways. Following this incident, several arsons occurred, and firefighters again struggled to find the location of the fire.

This prompted the Seaton Village Residents’ Association to create the Seaton Village Lane Naming Project. Local residents felt it was important to create street names that commemorated the historic significance of the neighbourhood. In 2014, after a local resident read James Fitzgerald’s book, the lane was officially named Crestfallen Lane to commemorate the memory of Dr. John G. Fitzgerald, Crestfallen the mare, the “miracle in a stable.”