Take a deep dive into medical history at U of T

By Meribeth Deen

Every one of us undoubtedly has a notable moment or story that reminds us of the moment when this pandemic “got real.” We are one year in, most of us are waiting for our vaccinations and for life to begin again. While we do, you may as well enjoy the COVID benefit of online exhibitions. The galleries and institutions that make up the Bloor St. Culture Corridor seem to have found their stride in this new world with a continuous flow of digital offerings.

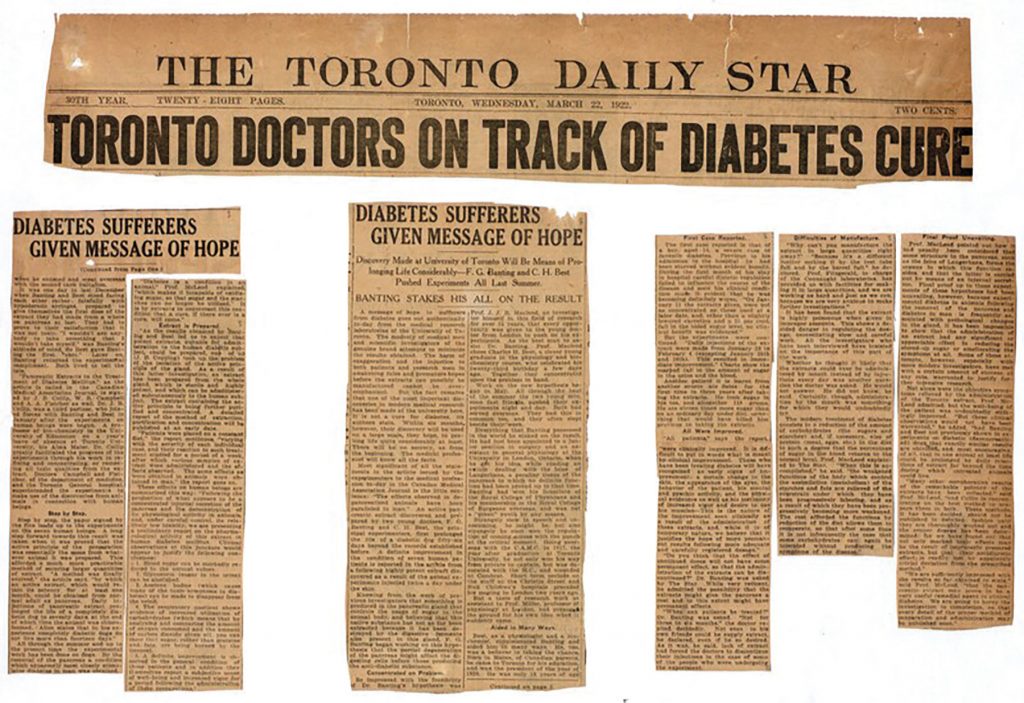

To celebrate the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin, the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library offers a deep dive into “one of the most dramatic adventures in the history of medicine” which offered the world a “miracle cure.” Curated by Alexandra Carter and Natalya Rattan, the exhibit relies on The Struggle for Glory, an essay published by the late professor of history, Michael Bliss.

We all know the name of Dr. Fredrick Banting, but did you know his decision to take up the research of the pancreas was made following a coin toss?

In the first section of the exhibition, on “The Discovery of Insulin at the University of Toronto,” you may read the paper that led to the idea that kept Banting up at night and had him asking for laboratory space at U of T in November of 1920.

At that time, it had been 30 years since diabetes had been linked to a problem with the pancreas. As Bliss writes, “therapeutic progress was excruciatingly slow.” One of the only treatments for diabetes that had come to the fore in that time period was a starvation diet, which would prolong life in young diabetics by a year or two.

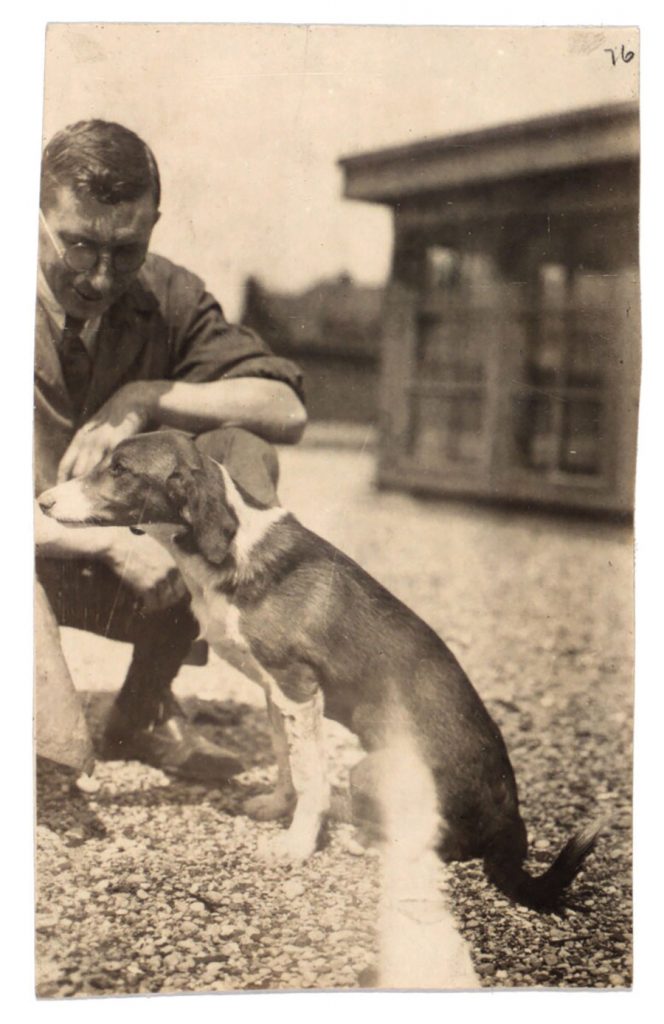

In the spring of 1921, Banting got the laboratory space he requested, some basic chemical equipment, a dozen dogs and two lab assistants. The assistants decided to split the shifts, and based on yet another coin toss, Charles Best took the summer stint. Flip through Banting’s notebook from those early days of research and do your best to decipher his doctor’s script.

The research was difficult to execute, which did not bode well for the dogs. To “replenish” they purchased dogs off the streets of Toronto for between $1 and $3.

In the summer of 1921, Banting and Best managed to keep “dog 92” alive for 20 days without a pancreas. It was one of many exciting disappointments that summer, and in the coming years they would hold on to the work done that summer as proof of their discovery. However, it would take years – and the work of other researchers – to purify insulin so that it could effectively lower the blood sugar of suffering diabetics, and no gain could seem to be made without an equal dose of drama. But by the autumn of 1922, the stories of “the awe-inspiring impact of insulin were beginning to multiply beautifully.”

A 15 year-old girl named Elizabeth Hughes became a “prize patient.” The girl’s letters to her mother are on display in this exhibit.

By the end of 1923, insulin therapy was available for people across North America and Europe. But that’s not the end of the story – The Struggle for Glory lay ahead.

To find out about that, and see the artifacts that tell the story, head over to the Thomas Fisher Library’s collection yourself.

Keep enjoying great works of local creativity online until you can get back into the buildings that make this city come alive.

READ MORE:

- ARTS: Embrace culture in defiance of COVID-19 (May 2020)

- ARTS: Culture Corridor adds members (May 2019)

- NEWS: Students solve mystery (April 2017)

- ABOUT OUR COVER: Arctic amusements (December 2016)

- ARTS: HMS Terror found on greeting cards (December 2016)

1 response so far ↓

1 Dr. Arthur E. Zimerman // Apr 2, 2021 at 11:14 am

Dear Ms. Deen:

One problem, as other researchers got closer to discovering that a peptide hormone was involved in treating diabetes, was they made a proper acid-ethanol extraction of pancreas, but they boiled it for sterilzing. The boiling destroyed the peptide hormone, and that threw them off track, because they were still thinkng that a toxin caused diabetes.

In my Ph.D. thesis at U of T, 1973, I did a thorough review of the expriments leading up to Banting’s breakthrough idea that finally proved that a protein hormone was the key. Worth telling that prelinminary part of the story, before anyone understood anything about protein or peptide homones.