Did James Lochrie install a cyclist path in 1896?

By Albert Koehl

On May 4, 2016, Toronto City Council approved pilot bike lanes on Bloor Street. Like many community initiatives, the vote was the culmination of work by individuals and groups that stretched over many years, in this case at least four decades. In fact, there is some evidence that the push for Bloor Street bike lanes goes back even farther — all the way to 1896 when businessman James Lochrie planned to install a cinder path for cyclists on Bloor Street West.

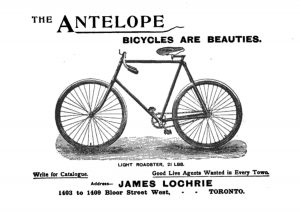

Picture Courtesy the Canada Lancet and Practitioner (1895): James Lochrie advertised his Antelope bicycles, which he began manufacturing in 1895, in a medical newsletter.

In the so-called bicycle craze of the 1890s, Toronto cyclists shared the road with horse-drawn wagons and buggies as well as horse cars, which soon became electric streetcars. The safety bicycle with its equal-sized wheels, chain drive, and pneumatic tires had replaced the perilous high-wheeler. A major obstacle for cyclists, aside from the high price of a bicycle, was the poor quality of roads. In the city’s central area, roads were being improved, sometimes with asphalt, but for Lochrie whose business and home were at 1403-11 Bloor St. W. — west of Lansdowne Avenue near the rail tracks — road improvements probably seemed a long way off.

On Feb. 17, 1896, The Globe reported that Lochrie intended to install, at his own expense, a cinder path on Bloor Street West. No specific area of the street is mentioned although the obvious candidate would be in the Junction, where Lochrie had his factory and home.

At the time, some cyclists considered cinder paths a good solution, although there was a lively debate between these cyclists and other cyclists who advocated for better roads all around. One problem with cinder paths was that heavier vehicles could be drawn to them to escape the poor quality of the rest of the road. The solution in Winnipeg, for example, was to prohibit conveyances other than bicycles from using these paths.

A case against the Grand Trunk Railway suggests that a cinder path on Bloor Street near Lansdowne Avenue was actually built. The court noted that the plaintiff Alexander Sims, an 18-year-old cabin maker, was cycling home from work in July 1903 along a “narrow pathway or bicycle track” on the south side of Bloor Street.

Sims was hit by a freight train and lost his leg. A jury awarded him $2,200 but the decision was overturned on appeal. “Death crossings”, as a December 1922 article in The Globe referred to level crossings, were replaced by overpasses in the area in 1925, partly due to advocacy by Lochrie’s son, David Alexander (or “D.A.”).

A photo in about 1900 from the City Engineer’s Office shows Bloor Street looking east across the tracks. The image includes a wooden sidewalk, the wide roadway, and what might be a cycle track on the south side.

Lochrie wasn’t a neutral bystander when it came to cycling.

In 1893 he filed for a patent for a treadle-like device to replace the pedals, crank, and chain. Around 1895 he began manufacturing Antelope Bicycles (without his new contraption), which he displayed at his showroom on Yonge Street or sold through agents in other towns. Ads for Antelope Bicycles, which embodied “the most significant improvements known in the art of Cycle building”, could be found in upscale publications, like The Dominion Medical Monthly.

Lochrie continued his bicycle-making business even after the dramatic fall in demand that began around 1899, a decline partly due to the falling out of fashion of bicycles among society’s upper crust. The major Canadian bicycle manufacturers at the time combined into a single company that became the Canada Cycle & Motor Company. The Canadian National Exhibition still listed Lochrie as a bicycle exhibitor in 1905. Lochrie also operated a bicycle livery and sold used bikes from his Bloor Street location until about 1908.

James Lochrie died in March 1930 at age 81. His residence was still shown as 1411 Bloor St. W.

Lochrie would likely have been pleased to hear about the new Bloor Street bike lanes, but surprised that it took so long.

Albert Koehl is an environmental lawyer, writer, and co-founder of Bells on Bloor. He is writing a book on climate change and sustainable transportation.

READ MORE:

NEWS: Bike lanes for Bloor Street (May 2016)

The faster we lower speeds, the more lives we save (October 2015)

Early brewer the basis for Bloor Street’s name (May 2015)