By Annemarie Brissenden

In apartheid South Africa, Black Beauty was banned from bookshelves.

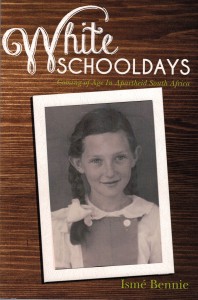

With the words “black” and “beauty” in the title, it was seen as some kind of anti-government propaganda, even though “there are no black people in the book.” Set in nineteenth-century England “it is actually about a horse,” writes Ismé Bennie in her new book, White Schooldays.

The Harbord Village resident, who has lived in the area since 1973, began her career as a librarian in South Africa before immigrating to Canada, where she became a successful broadcaster, eventually running several specialty channels for CTV. But she always wanted to be a writer, and has collected a series of essays into a self-published memoir about growing up in South Africa during the 1940s and 50s.

The daughter of Jewish immigrants who fled the pogroms of Eastern Europe, Bennie was brought up in Vereeniging. Although her family was not particularly religious, they stuck largely with the close-knit white Jewish community that populated their neighbourhood.

Organized as a series of vignettes on different topics from the serious — how her family came to South Africa, being Jewish, and going to school — to the light-hearted — pets, food, and literary loves — White Schooldays provides a glimpse into her privileged world.

Bennie was a white child who unquestioningly accepted her segregated existence, and her descriptions read as an authentic reflection of her childhood naïveté.

After talking about how girls were required to take a domestic science class in high school that included sections on how to treat servants, she relates how “we illustrated our Dom Sci notebooks lavishly, mainly with cutouts from advertisements in US magazines.

“For my notes on handling the help, I remember my illustration came from McCall’s or Ladies’ Home Journal, and I had captioned it ‘The ideal servant.’ It was a beaming Aunt Jemima.”

In another anecdote, her mother, who didn’t drive, had to jump through several bureaucratic hoops to get permission for Daniel, her black driver, to take her to the white drive-in to see a movie.

“After the show she asked Daniel how he had enjoyed the experience. Turned out he had already seen the film in Sharpeville!” recounted Bennie.

In such moments, some additional commentary might be called for: how the Aunt Jemima character idealized slavery in the American South, or that Sharpeville was home to a large black community and the site of a massacre in 1960. However, the absence of commentary in these vignettes does help to evoke the pervasive ignorance of the context in which she was raised.

“I wasn’t exposed to anything that made me politically aware,” admitted Bennie during an interview, adding that she “wanted to put it down on paper to show what it was like.”

As Bennie grew older, political activism, however, crept into the corners of her existence.

Her university residence backed onto a main thoroughfare where “women of the Black Sash — a non-violent white women’s resistance organization — [would stand] on its sidewalks in silent vigil to protest the apartheid government’s moves to set up a separate school system for non-whites.”

And for stories set later on chronologically, Bennie narrates from a more mature, politically aware perspective.

She talks of flying back to South Africa in 1980 to visit her 80-year-old father, who was living in a Jewish nursing home. He is cared for by “black maids — black women still the caregivers of the whites, when they are young children and when they become helpless old men.”

In another section she writes of attending university:

“I see now that I was amongst the privileged, that I was living and learning in a parallel universe, and that millions of black kids were denied my kind of education. If only they had been allowed the same opportunities, South Africa would be a very different country.”

These days, Bennie is pessimistic about the future of the place she calls home.

“I’m not happy about the current state of affairs,” she said. “There’s a huge economic divide, and I can’t see any immediate resolution. There are too many insurmountables.”

Her sister lives in Johannesburg, which Bennie describes as a society built on fear, in which residents live a limited existence.

But, there are some experiences that remain positive.

“I get tremendous pleasure when I go to a restaurant or shopping mall, and it’s totally mixed these days.”

White Schooldays: Coming-of-Age in Apartheid South Africa is available as an e-book from Amazon.ca.